By Alexis Fessatidis

In the last two decades, briefings by women civil society have become a regular, deeply-rooted, well-established practice[1] of the UN Security Council—so much so that 2021 saw a record high of 62 women civil society briefers. Since the adoption of Resolution 2242 (2015) in particular, which expressed the Council’s intent to invite civil society briefers on both country-specific and thematic discussions, women civil society’s participation at the Security Council has steadily increased. In recent years, Security Council members have taken specific steps to prioritize the participation of women civil society, including through the Shared Commitments on Women, Peace and Security (WPS Shared Commitments) initiative, started by Ireland, Kenya and Mexico in 2021, and expanded under Norway’s leadership in 2022. Today, as part of this continuing initiative, 20 former and current Security Council members[2] have committed to ensuring the safe participation of civil society briefers in Security Council meetings, a zero-tolerance approach to reprisals against such briefers, and follow-up on the recommendations and priority issues they raise.

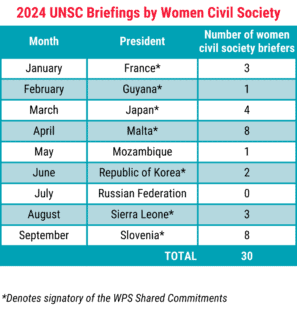

Yet for the second year in a row, the participation of diverse women civil society at the Council has declined. In 2022, there were 56 women civil society briefers and in 2023, that number decreased to 45, a 27% decline compared to the record high in 2021. Nine months into 2024, there had only been 30 women civil society briefers.[3] With just a few months left before the end of the year, we hope this downward trend will not continue for a third year in a row.

We know this is not a numbers game—while it’s important for the Security Council to ensure that civil society are included as often as possible in its discussions, inviting women civil society briefers should not become a superficial exercise for its own sake. As representatives of affected communities, and as individuals who bring unique expertise and raise issues that may otherwise be overlooked, it is critical that women civil society not only continue to be regularly invited to brief the Security Council on all topics on its agenda, but that their perspectives and recommendations meaningfully inform the Security Council’s work.

Lower numbers of women civil society briefings mean that Security Council members hear less and less from the women whose lives are affected by their decisions. By the end of September, the Council still had not yet heard this year from any women civil society from the Central African Republic (CAR), Haiti, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Myanmar, Palestine, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria or Ukraine.[4]

Lower numbers of women civil society briefings mean that Security Council members hear less and less from the women whose lives are affected by their decisions.

There are several possible reasons why these voices aren’t being heard: difficult political dynamics (whether in the country in question or within the Security Council itself); fear of reprisals against civil society for speaking out; or failure to prioritize hearing from civil society in specific conflicts. The absence of civil society voices from contexts on which the Council meets more regularly, including Syria, Palestine and Ukraine, is particularly striking. In other cases, the termination of peace operations (such as in the case of Mali) or the fact that the Security Council does not typically meet in open session (such as Myanmar) means that civil society generally has fewer opportunities to participate in Council meetings.

Briefers invited under the agenda item “the situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian Question,” offer a telling example of several of these factors at play. Palestinian women civil society leaders have been noticeably absent from the Security Council—not just since the 7 October 2023 attacks by Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups, and Israel’s subsequent hostilities in Gaza, the West Bank and now the region. No Palestinian women civil society have briefed the Security Council since January 2022. When they have been invited to brief under this agenda item,[5] they have only been invited to do so alongside Israeli civil society briefers, a dynamic we rarely see in other conflicts and crises on the Security Council’s agenda, but which was ostensibly viewed as a means to navigate the highly politicized nature of this conflict. Since 7 October 2023, this politicization—and fears of reprisal against those who speak out against Israel’s military campaign—has become particularly acute. In February 2024, during a civil society briefing on this crisis, the Secretary General of Médecins Sans Frontières described the attacks Israel has carried out against humanitarian staff on the ground, including bulldozing vehicles, detaining staff, and bombing and raiding hospitals, expressing to the Council “Our colleagues in Gaza are fearful that, as I speak to you today, they will be punished tomorrow.” On 4 September, Israeli human rights activist and Executive Director of B’Tselem, Yuli Novak, briefed the Security Council on the situation in the West Bank and Gaza, describing Israel’s “policy of massive harm to civilians and civilian infrastructure” in Gaza. Shortly after, Israel’s Ambassador to the UN accused her of “spreading lies” on X; within days, Israeli lawmakers had called for her to be detained and interrogated, stripped of her citizenship, imprisoned for life or even executed.

No Palestinian women civil society have briefed the Security Council since January 2022.

Three Iraqi women civil society briefed the Security Council in 2023; none have briefed in 2024. This comes against the backdrop of a severe crackdown on civic space in Iraq, particularly against women’s and LGBTQI+ groups, including a ban on the use of the term “gender” and directive to replace the term “homosexuality” with “sexual deviance,” further anti-LGBT legislation and general restrictions on freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.

No women from CAR have briefed the Security Council since June 2022. Briefings at the Council by women from South Sudan have tapered off from three in 2021 and five in 2022, to just one in 2023 and none thus far in 2024. Pervasive intimidation, threats and attacks against human rights activists, civil society, journalists and members of the public are well known and documented in CAR and South Sudan, though we do not know the scale of this issue due to underreporting because of fear of further reprisal.

As the UN prepares for the eventual transition of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) at the request of the government, only one Somalian woman civil society representative has briefed the Security Council since November 2021 (though there were four Somalian women briefers that year). Her briefing happened on 3 October, almost three years since the last Somalian woman civil society briefing, and despite the importance, as stated in Resolution 2594 (2021),[6] of ensuring comprehensive gender analysis and the meaningful participation of women during mission transitions. A rare, but important, moment of transparency at the Council provides some insight into why briefings by Somalian women have been so infrequent: during a WPS-focused geographic meeting on Somalia under Malta’s Security Council presidency in February 2023, Malta expressed deep disappointment that conditions had not been “conducive to the safe participation of a [Somalian] civil society representative to brief the Security Council on WPS issues,” called for the Council to do more to enable civil society’s safe participation free of fear of reprisals, and circulated a statement to Council members on behalf of the civil society network they were aiming to support in briefing the Council. With plans for UNSOM’s transition underway, there will likely be fewer opportunities for Somalian women civil society to brief the Security Council.

Even invitations to Afghan women, who have historically briefed the Security Council more often than women civil society from any other conflict or crisis on the Council’s agenda, have declined. In 2021, there were seven briefings at the Security Council by Afghan women, and in 2022, eight. Yet, as the Taliban’s abuses against women and girls have deepened, and despite repeated affirmations by the Security Council of the importance of consultation with Afghan women and their full, equal, meaningful, and safe participation,[7] only three Afghan women briefed the Security Council in 2023. Of the three Afghan women who have briefed thus far in 2024, it would appear that Council members have invited individuals to address topics such as the economy, girls’ education, or engagement with the Taliban, which are more aligned with the UN-led Doha process and seen as less likely to fragment the Security Council.

Although the Taliban’s abuses against women and girls have deepened, only three Afghan women briefed the Security Council in 2023.

Two and a half years since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, only five Ukrainian women civil society representatives have briefed the Security Council—four out of their five briefings happened in 2022 and no Ukrainian women civil society have briefed the Council since August 2023. Meanwhile, in the last two and a half years, the Council has heard from at least 30 briefers invited by the Russian Federation, largely under meetings called by Russia to discuss the supply of Western weapons to Ukraine, or developments related to the September 2022 Nord Stream pipelines explosions. The overwhelming trend with such briefers invited to the Council by Russia has been that they appear to be individuals briefing on their own behalf, often without tangible links to independent and verifiable civil society organizations, and without specific expertise on the situation in Ukraine, or peace and security issues.

In 2022, four Malian women civil society briefed the Security Council; in 2023, this number dwindled to two, the same year the Malian authorities requested withdrawal of the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). A very public reprisal against one of those briefers, Ms. Aminata Cheick Dicko, in January 2023, illustrated the grave threats to the safety of those Malian civil society who do speak out. Following her briefing to the Council, the Malian Minister of Foreign Affairs publicly questioned her credibility and the Malian military issued a legal complaint against Ms. Dicko with allegations of defamation and high treason, instigating a social media smear campaign with threats to her life. Security Council members convened in a closed meeting to discuss the reprisal, signaling the Council’s acknowledgement of the severity of the case. Without a regular reporting mandate on Mali since the termination of MINUSMA in June 2023, the Security Council no longer meets regularly to discuss the situation in Mali, meaning that civil society briefings by Malian women would only occur under thematic discussions—none have happened so far.

A public reprisal against Aminata Cheick Dicko in January 2023 illustrated the grave threats to the safety of Malian civil society who speak out.

The reprisal against Ms. Dicko was an unusually public example of a trend women civil society know all too well—that speaking out (or on specific topics) can often result in reprisals designed to silence them. Over the years, the NGOWG has worked to enable women from conflict contexts to engage directly with decisionmakers at the UN, and particularly to brief the Security Council. In January 2022, we briefed the Security Council at the first-ever open debate dedicated to protecting women’s participation and addressing violence targeting women human rights defenders, including to describe the severity and scale of reprisals we have witnessed against women civil society for briefing the Council. As we described, the women we have worked with have faced a variety of reprisals, including threats, censorship, verbal attacks in the Security Council chamber, smear campaigns, defamation, arbitrary detention by security forces, abduction of support staff, and targeting of family members. In some cases, individuals needed to be temporarily, or even permanently, relocated for their safety. These reprisals, which occurred in retaliation for their work as women human rights defenders and their briefings to the Security Council, reflect a broader pattern: a UN Women survey of women civil society who briefed the Security Council in 2023 found that 5 out of 23 respondents (22%) reported reprisals in connection to their briefings. These numbers likely represent only a fraction of such cases—attacks against women human rights defenders are extremely underreported, not least of all because of fear of further reprisal.

In the almost two years since the reprisal against Ms. Dicko, we have seen many well-intentioned entities, including the UN and Security Council members who are part of the Shared Commitments on WPS, become so concerned about reprisals that they have inadvertently limited civil society participation, rather than mobilizing resources, funds and coordinated action to address risks to civil society. In some cases, briefings deemed “too risky” have been pulled at the last minute, if they are even attempted at all. In other cases, Council members have sought voices from outside the country in question or even an entire region, or have invited women civil society who have already briefed the Council or who are well-known in these spaces, presumably because they are viewed as more acceptable or less at risk. Council members are also increasingly choosing civil society briefers whose views are seen as less sensitive or that align with those of the inviting Council member themself, rather than supporting briefers that can offer independent, unvarnished analysis, including by ensuring that they are selected and supported by civil society organizations.

Many well-intentioned entities have become so concerned about reprisals that they have inadvertently limited civil society participation.

We can see the effects in the profile of those who are briefing the Council—while the number of women civil society briefers has decreased overall, the number of women civil society briefers who do not represent affected communities (whether in country, in the diaspora or in exile) has steadily increased. In 2021, 16% of the women civil society representatives at the Council represented international NGOs or NGOs from the Global North, came from the Global North, or otherwise did not represent an affected community. In 2023, this number jumped to 24% of women civil society briefers and so far in 2024, 50%.

Of course, there are legitimate reasons why Security Council members may choose to hear from briefers from international NGOs or the Global North, including on specific issues where an expert or academic perspective might be important, as well as when risk precludes inviting civil society working at the national or local levels. But hearing from women from affected communities, whether they are in-country, in exile or in the diaspora, should generally be a first priority, and no longer seems to be.

The cumulative effect of such selectivity being applied to civil society briefers is that the Security Council is hearing less and less from women from the conflicts and crises on its agenda—the women at the heart of the WPS agenda. Supporting their safe participation at the Security Council, and implementing a zero-tolerance approach to any form of attack, intimidation, retaliation or reprisal against them,[8] is a critical way to ensure that their crucial perspectives inform the work of the Security Council.

Civil society briefers undoubtedly take risks to share their perspectives in public fora—they are targeted for who they are, and the work they do in speaking out against injustice and abuse. But managing risks and thinking carefully through protection, while important, should never compromise women civil society’s participation or censor their independent views. A zero-tolerance approach to reprisals does not mean zero risk—it means effectively managing risks by investing political and financial capital in enabling women civil society to participate. The UN and Member States have a shared responsibility to enable such participation by preventing, addressing and responding to reprisals against women civil society.

Protection, while important, should never compromise women civil society’s participation.

Recommendations

Member States should:

- Protect, support and recognize the legitimacy of women civil society, including by elevating their role in promoting peace and human rights, and eliminate any restrictions or barriers to their work.

- Continue to support regular, diverse and independent women civil society participation at the Security Council, including women from conflict-affected countries and individuals representing diverse ability, ethnic, racial, sexual orientation and gender identity backgrounds and perspectives, at all relevant discussions, including country-specific meetings, in line with Resolution 2242.

- Reject any efforts that seek to undermine the independent selection and views of women civil society invited to brief the Council.

- Amplify and follow up on the recommendations and priorities raised by women civil society.

- Ensure robust implementation of a zero-tolerance approach to reprisals, by taking all necessary measures to protect women civil society representatives who brief the Council and ensuring that their perspectives, rights and needs are centered in all efforts to mitigate and respond to reprisals. These measures should include:

- Conducting risk assessments in coordination with relevant UN agencies and civil society partners before their briefings, and developing mitigation plans and strategies in order to address any risks identified;

- Designating a focal point within Member State Missions to lead on reprisals, sensitize other colleagues on the issue and develop a chain of command to address risks;

- Where possible, assisting other Council members with, and particularly coordinating amongst the signatories of the WPS Shared Commitments on, protection measures, including by sharing advice, resources, lessons learned and best practices. This includes sensitizing new signatories of the WPS Shared Commitments to ensure they understand what a zero-tolerance approach to reprisals requires of them;

- Allocating funding within Member State Missions to support the safe participation of diverse women civil society briefers at the Council and to respond in case of reprisals against them;

- Periodically following up on the security of briefers after their briefings;

- Urgently responding to reprisals when they occur, including by providing rapid, flexible and targeted resources where necessary, and advocating privately or publicly for the individual at risk, depending on context and in close consultation with the individual.

- Call on the UN system to adopt a more systematic, coordinated approach to the issue of reprisals. This includes establishing clear protocols for and a meaningful scaling up of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and other relevant UN agencies’ capacity to monitor, report on, prevent, respond to and follow up on cases of reprisals against women civil society representatives at the Security Council. In this regard, signatories of the WPS Shared Commitments could meet with OHCHR at the highest levels, including with the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the Assistant Secretary-General for Human Rights, to discuss challenges in addressing the security of women civil society at the Council and to identify concrete strategies to enable their safe participation.

- Ensure that all peace operations are mandated, fully resourced and empowered to monitor, report on and respond to attacks and violence against women human rights defenders and peacebuilders, including by providing systematic and scaled-up support to those at risk in order to effectively prevent and respond to such violence.

Alexis Fessatidis is the Advocacy and Program Manager at the NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security.

Photo Credit: UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe

[1] According to the NGOWG’s internal analysis, the Security Council has recognized the importance of civil society more than 650 times in 385 separate resolutions and has explicitly invited civil society to brief the Council in at least 8 outcome documents spanning various thematic agendas.

[2] The 20 former and current Security Council members who have signed the WPS Shared Commitments are Albania, Brazil, Ecuador, France, Gabon, Guyana, Ireland, Japan, Kenya, Malta, Mexico, Niger, Norway, Republic of Korea, Sierra Leone, Slovenia, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States.

[3] Under Rule 39 of the Security Council’s Provisional Rules of Procedure, the Security Council “may invite members of the Secretariat or other persons, whom it considers competent for the purpose, to supply it with information or to give other assistance in examining matters within its competence.” It is under this rule that civil society speakers are invited to brief the Council. The NGOWG’s count of women civil society briefers at the Security Council comprises only those briefers invited under Rule 39 who are explicitly members of women civil society—that is, who brief the Council in their capacity as an individual or on behalf of a local, national, regional or international non-governmental or nonprofit organization or network that is nonviolently promoting human rights, gender equality and/or peace, and contributing to positive social change for their communities. This includes women leaders, peacebuilders, human rights defenders, journalists, academics, experts or representatives of social movements advocating for or otherwise contributing to the promotion of human rights and peace. The NGOWG’s civil society briefer numbers do not include: individuals with clear links to a Member State or Member State-run entities; politicians; religious figures or leaders; celebrities; individuals who work in the private sector or business; individuals representing UN entities or regional or intergovernmental bodies; individuals who serve as Ambassadors, Champions or Envoys for Member States, UN entities or regional or intergovernmental bodies. Individuals that do not meet the definition above may be invited to brief the Security Council under Rule 39 but are not necessarily considered independent and genuine civil society representatives.

[4] In October, the Security Council heard from the first Libyan and Somalian women civil society briefers this year, under the presidency of Switzerland.

[5] In October 2018, the NGOWG supported Randa Siniora to brief the Security Council at the Open Debate on WPS. She was the first Palestinian woman civil society representative to ever brief the Council, and to date, is the only Palestinian woman to brief the Security Council without an Israeli briefer alongside her.

[6] Resolution 2594 calls on the Secretary-General to “ensure that comprehensive gender analysis and technical gender expertise are included throughout all stages of mission planning, mandate implementation and review and throughout the transition process, as well as mainstreaming of a gender perspective, and to ensure the full, equal, and meaningful participation of women, and the inclusion of youth.”

[7] See, for instance, Security Council resolutions S/RES/2626 (2022); S/RES/2679 (2023); S/RES/2681 (2023); and S/RES/2721 (2023).

[8] Statement of Shared Commitments on Women, Peace and Security, https://ambasadat.gov.al/united-nations/ova_dep/albanias-priorities-in-the-council/; Report of the Secretary-General on Cooperation with the United Nations, its representatives and mechanisms in the field of human rights, 20 August 2024, https://undocs.org/A/HRC/57/60.