Over the past year, Iraqi women and girls, including those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT), have faced increasing violence and discrimination as a result of the deteriorating security, political, and economic situation, which has worsened in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The existing barriers to accessing basic social services such as health care, which triggered protests over the last two years, have compounded the risk of contracting COVID-19 for women and girls who undertake greater domestic care responsibilities.

Women disproportionately suffer from high rates of violence (which includes domestic violence) forced marriage, sex trafficking, and gender-based violence in internally displaced person (IDP) camps. The recurring violence experienced by women, girls, including those who identify as LGBT, results from widespread patriarchal social and cultural norms, lack of awareness regarding the government’s obligations to safeguard and promote women’s rights in accordance with international humanitarian and human rights law, and institutional and legal barriers to gender equality and justice.

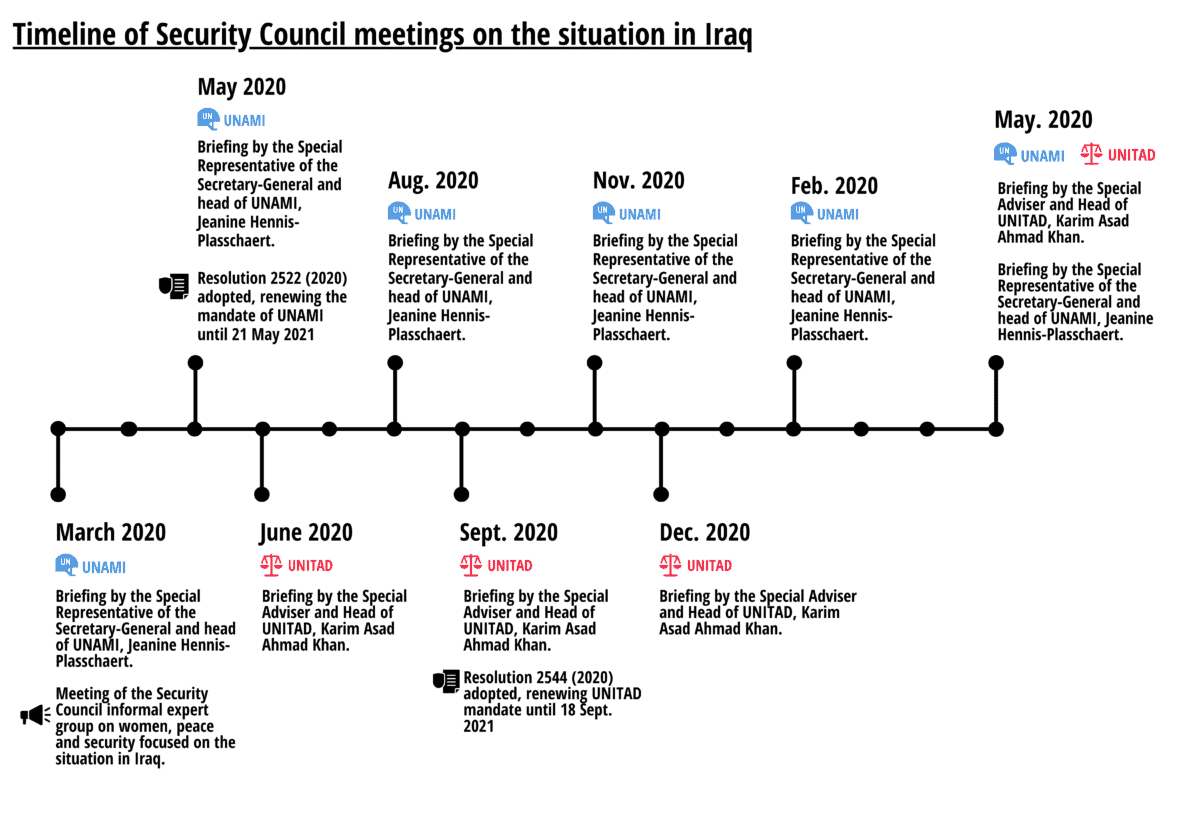

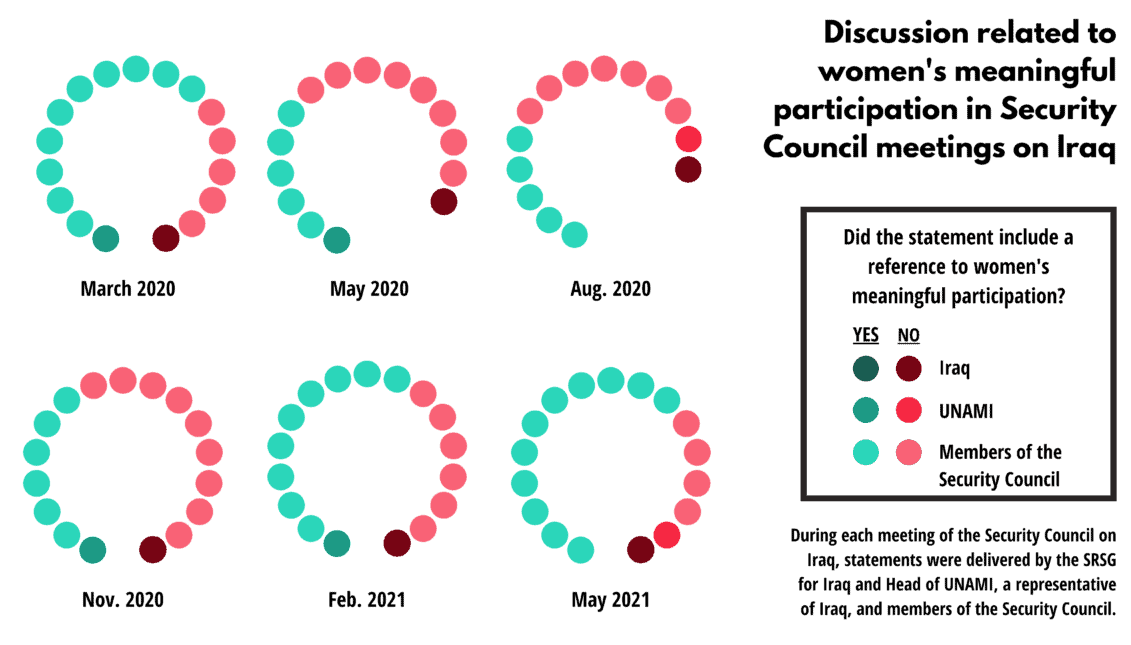

Women, peace and security was discussed more frequently by the Security Council in its meetings over the course of 2020, influenced in part by the meeting of the Security Council informal expert group (IEG) on Iraq in March 2020, as well as information on WPS in the regular reports of the Secretary-General focused on the work of the UN Assistance Mission in Iraq (UNAMI).[1] The statements of Council members from March 2020 to May 2021 clearly showed the influence of these two sources of information. The provisions in the mandate of UNAMI related to WPS were not substantively improved; the Council missed an opportunity to reflect some of the key issues raised in the IEG meeting.

Despite the positive attention to WPS broadly, the specific focus of the references was often narrow and nearly identical across all Council member statements. It is important to have unified support for core WPS issues and goals; however, the short list of distinct WPS issues, and the uniformity of the items, referenced in Council members’ statements suggests that Council members might view these issues as “checkboxes” for their statements.

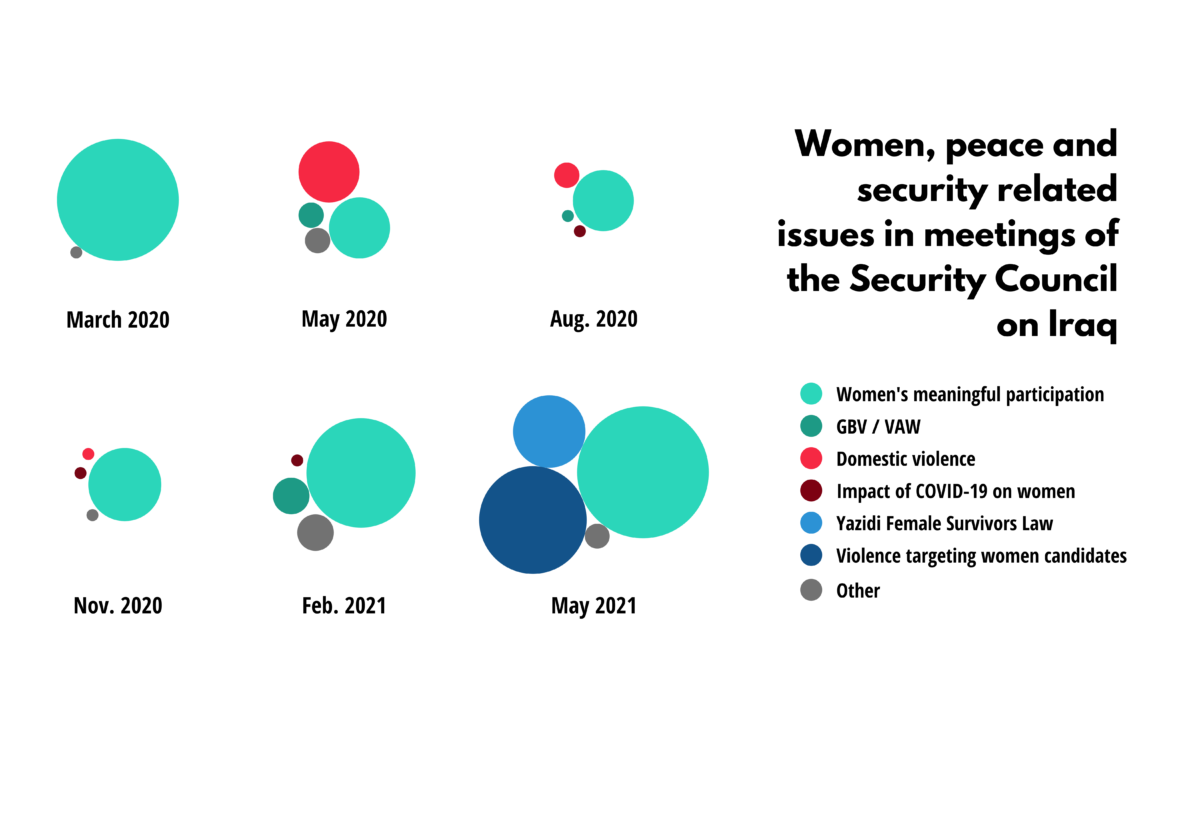

Expressions of support for women’s meaningful participation in governance and political processes was the issue most consistently raised by Council members over the course of the period under review, with attention shifting to women’s participation in electoral processes as electoral reform processes developed. Positively, in March 2020, there was considerable attention to the important role of women in the protests taking place throughout Iraq.

Notably, the inclusion of information related to efforts to address violence targeting women candidates for public office in the report of the Secretary-General in April 2021 led to strong references to that issue by multiple Council members in May 2021; the Council has often overlooked this topic in previous discussions on country situations including Iraq.

Gender-based violence and access to justice

Throughout the Security Council’s discussions on the situation in Iraq, attention to gender-based violence and justice often was narrowly focused on violence carried out by non-state armed groups. GBV, including domestic violence, forced marriages, sex-trafficking, so-called “honor killings,” and sexual violence in IDP camps remains a serious concern. The COVID-19 pandemic, which arrived in Iraq in February 2020 (OHCHR), has triggered an increase in domestic violence and forced marriages in the country by increasing political instability and economic insecurity in the country (Cordaid, HRW). Iraqi women and girls have found themselves confined to their homes with their abusers and with little access to public services such as shelters, education, formal employment, and health care.

Throughout Iraq, women continue to face barriers to justice due to a range of factors. First, Iraq’s discriminatory legal system fails to hold perpetrators accountable and enables impunity by excluding marital rape as a criminal offense, and failing to define key crimes, such as “forced marriage” and “consent.” This, combined with the lack of comprehensive and effective anti-domestic violence legislation and limits placed on mobility, due in part, to patriarchal social and cultural norms and the COVID-19 pandemic, result in not only a system which is challenging to access, but also an environment in which GBV is significantly under-reported, and fear of retaliation by perpetrators and/or authorities is widespread.

As a result, perpetrators of sexual violence can marry their victims and acquire legal impunity. Iraq’s discriminatory legal infrastructure violates its commitment to safeguarding Iraqi women and girls from discrimination under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and Security Council Resolution 1325. The Iraqi government has not implemented comprehensive and effective anti-domestic violence legislation despite the introduction of a national anti-domestic violence law to Parliament in 2015. Although this draft law focuses on the provision of reconciliation services to survivors of domestic violence rather than on ensuring their access to protection and justice, it would serve as progress in safeguarding Iraqi women and girls from domestic violence if the Iraqi Parliament passes it.

The Kurdistan Regional Government created the Directorate of Combating Violence Against Women (DCVAW) in 2007 to respond to GBV cases, and passed its own domestic violence law in 2011, but a lack of awareness and social willpower to abide by the provisions of this law has made this law difficult to implement in the Kurdistan region (Oxfam, Cordaid). Although the Kurdistan Regional Government offers safe spaces and shelters for survivors of GBV, women in the Kurdistan region face restrictions on their mobility when trying to communicate with authorities and seek assistance outside of their homes (UN Women). The uptick in domestic violence in Iraq during the past year is made more disturbing by the fact that, as of 2006/2007, one in five Iraqi women had already reported having experienced domestic violence in her lifetime (HRW). The Iraqi government has not reestablished courts to oversee GBV and domestic violence cases since they terminated these courts in 2017. The Iraqi government has also failed to improve its family protection units, which operate out of police stations under the Federal Ministry of Interior. These units are mostly composed of male police officers, which deters many women and girls from coming forth to report their experiences with GBV out of a fear of judgment and retaliation. These units also lack adequate resources to help process and respond to Iraqi women and girls’ complaints in the long term.

Iraqi families continue to marry off women and girls in exchange for financial compensation and/or out of the perception that women and girls will achieve greater economic security through marriage. Forced marriages often leave Iraqi women and girls susceptible to domestic violence and GBV by dismantling their right to autonomy and access to resources.

Women and girls believed to be affiliated with ISIS face particular stigma throughout the country. So-called “honor” killings remain common throughout the country, especially towards women and girls who communities believe had affiliations to ISIS, even if their affiliation was forced marriage or is nonexistent. So-called “honor” killings are also often underreported throughout the country due to the framing of them as accidents or suicides.

Sexual violence in IDP camps remains a critical problem throughout Iraq and has particularly harmed women and girls from minority groups such as the Yazidis who have unsuccessfully sought reintegration into Iraqi society. Local authorities, administrators at IDP camps, and security forces have used sexual violence against women and girls from ethnic groups such as the Yazidis (in addition to denying them identity documents which they need to access employment and reintegration services) as retribution for the perceived affiliation of these women to ISIS. The discrimination that women and girls face in IDP camps for their perceived affiliation to ISIS re-traumatizes women and girls who were held captive under ISIS, and has led women and girls to experience acute psychological distress, depression, and anxiety.

In March 2021, the Iraqi government passed the Yazidi Female Survivors Law, which recognizes that ISIS’ systematic GBV against Yazidi women in its controlled territory amounts to genocide and promises Yazidi survivors reparations for the trauma they endured from ISIS fighters. Over the course of the meeting of the Security Council in May 2021, six Council members recognized the adoption of this law, reinforcing its importance as a step towards accountability. This public recognition of progress during Council members is critical; however, continued attention to its implementation in future meetings by Council members remains essential.

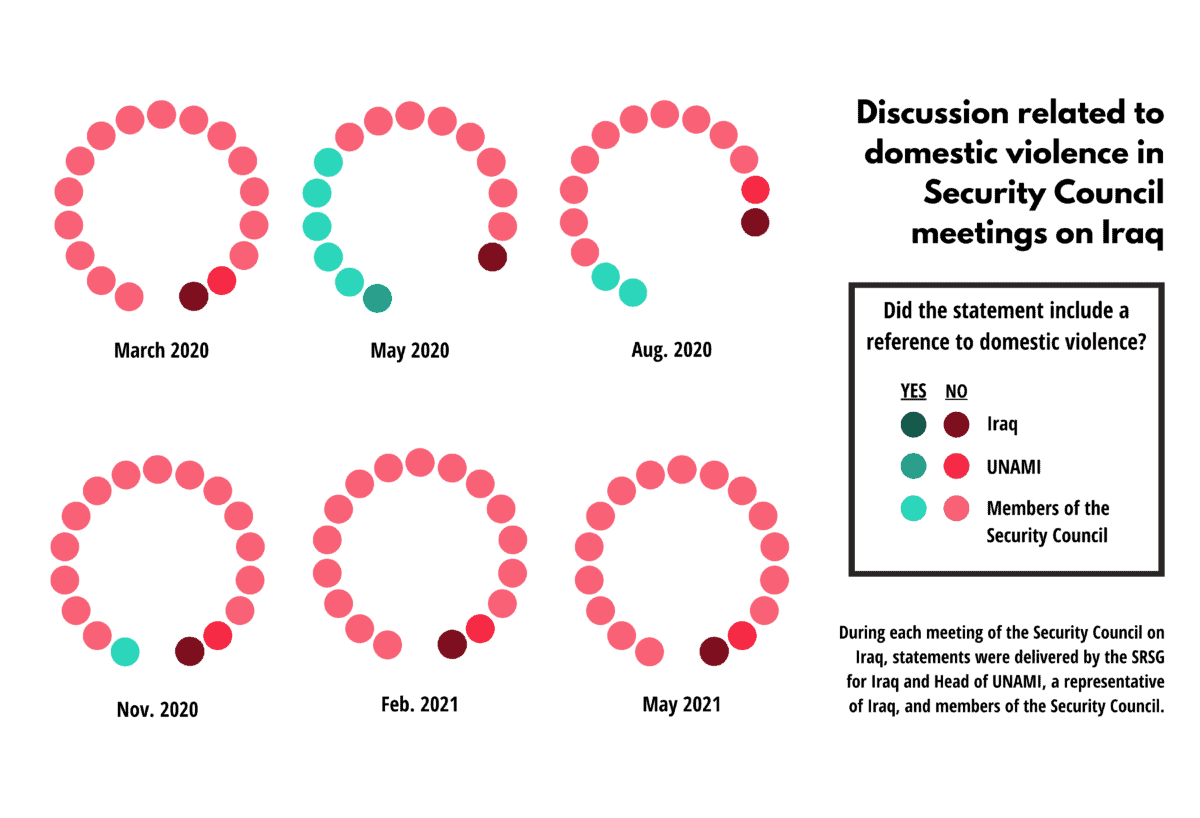

Overall, issues related to gender-based violence were discussed sporadically in the Council, with a notable spike in references in May 2020, coinciding with particular attention to the increase in domestic violence resulting from the measures undertaken to prevent the spread of COVID-19. However, despite domestic violence continuing to be a significant issue of concern; all mentions of the issue ceased by the end of 2020.

Discrimination Against LGBT Women and Girls

Discrimination against LGBT women and girls is frequent, normalized, and under-reported in Iraq. Although issues related to LGBT women and girls were raised in several contexts, including the March 2020 meeting of the IEG on WPS, the issue has been completely ignored by Security Council members in adopted outcomes and meetings.

Discrimination against LGBT women and girls takes the form of verbal abuse, physical violence, and forced marriages, as families marry off LGBT women and girls to “convert them.” LGBT women and girls face barriers in accessing health care and other basic services. There are multiple factors that contribute to this discrimination. Communities throughout the country regard LGBT women and girls as purposely defying social norms and bringing dishonor to their families by identifying as LGBT. The Iraqi media reinforces these norms through biased coverage against LGBT individuals. The lack of legal protections for LGBT individuals and the existence of laws that foster violence against LGBT individuals also contribute to this discrimination.

Governmental entities have failed to ensure any protection for LGBT individuals, often directly and indirectly contributing to an environment in which violence is carried out and the rights of LGBT persons are undermined. Government officials’ actions have legitimized targeted campaigns against LGBT individuals. Of the violence reported against LGBT individuals from 2015 to 2018, the Iraqi government and its affiliates accounted for 53% of this violence. This is an extremely concerning development. given that the Iraqi government committed to protecting its citizens who identify as LGBT by ratifying international human rights law provisions such as CEDAW.

Recommendations

The Security Council should:

- Insist on the passage of comprehensive and effective anti-domestic violence legislation through Iraq’s Parliament that will equally prioritize protection and reconciliation services and women and girls’ access to justice.

- Add a provision in UNAMI’s mandate, which requires the mission to regularly and meaningfully consult with women’s civil society groups in all aspects of its work, particularly in supporting capacity-building of essential civil and social services, many of which are being carried out by frontline women’s civil society organizations.

- Add a provision in UNAMI’s mandate requesting gender-responsive monitoring and public reporting, as part of its human rights mandate, on the abuse and use of lethal force against Iraqi civilians protesting and efforts to restrict and close civic space, including for women’s rights groups (AI, UNAMI, Al Jazeera, AP). Council members should also support calls of Iraqi civil society organizations (CSOs) to follow this up with an impartial and transparent mechanism to hold perpetrators accountable.

- Call on the Government to ensure its response to the COVID-19 pandemic is gender-responsive, meaningfully includes women’s perspectives, and is grounded in an evidence-based gender-sensitive analysis (AI).

- Call on the Government to enforce the rule of law and immediately stop, but also prevent, the violence, including sexual and gender-based violence, and use of excessive force, mass arrests, and attacks by security forces against demonstrators and other civil society actors, such as journalists and human rights defenders, including under the pretext of emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Call on the Government to urgently enact the Protection Against Domestic Violence law with a provision that ensures civil society engagement and legally recognizes civil society-run safe homes. This is especially important in the context of the rising rates of gender-based violence (GBV) linked to confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic (UNFPA, HRW, UNFPA, OHCHR, UNICEF, UN Women, CEDAW).

- Call on UNAMI to prioritize GBV programming and response in its role mobilizing and coordinating funding to concretely advance survivor-centered approaches to GBV, including supporting efforts to develop confidential reporting mechanisms, advancing the urgently needed domestic violence legislation, and supporting the establishment of NGO-managed shelters for survivors. GBV programming must also take into account the perspectives of LGBT individuals in planning and implementation (OutRight Action Intl.).

[1] Please note, the focus of this analysis is primarily on the Security Council’s discussion as it pertains to UNAMI, not the work undertaken by UNITAD.