Accountability for implementation of the WPS agenda

Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women, October 2019

Key Messages

As outlined at the start of this document, accountability of all actors, particularly Security Council members and Member States, for WPS implementation, is critical to advancing the agenda. Recommendations to Security Council members on priority areas are outlined throughout this report.

System-wide accountability of the UN for WPS implementation is equally important. As noted by the Secretary-General, in the five years since the three peace and security reviews were conducted, out of 30 total WPS recommendations for which the UN is the primary implementing stakeholder, only 50% have progressed, and only two recommendations have been fully implemented.[1] The independent assessment that reviewed progress in implementing the WPS recommendations and informed the findings of the 2019 report of the Secretary-General highlights multiple recommendations as requiring progress or actively regressing, including:

- Accountability of senior UN leadership;

- Participation of women in UN-backed peace processes;

- Inclusion of gender provisions in peace agreements;

- Strengthened gender-sensitive conflict analysis and its application for planning and resource allocation;

- Recruitment of senior gender advisers across the UN system;

- Consultations with women’s civil society organizations across peace and security settings and in humanitarian responses to inform analysis, planning and monitoring of progress and implementation;

- Allocation of a minimum of 15% of peacebuilding funding to gender equality and women’s empowerment, and the ability of entities to track and report on gender equality funding allocations.

This assessment also identified three factors influencing lack of implementation of the above recommendations:

- The degree to which gender and WPS is prioritized and resourced;

- The availability of gender expertise to drive progress at senior levels and across political and technical components;

- The lack of accountability for meeting WPS commitments across the UN system.

In 2020 and beyond, the NGO Working Group (NGOWG) will prioritize advancing several of the key recommendations from the three peace and security reviews that are regressing or where further progress is needed, as well as recommendations aiming to address the three factors identified as the root causes for failure to fully implement WPS by the UN system. The lack of accountability across the UN on WPS was highlighted as a key factor contributing to lack of implementation; the NGOWG will, therefore, advocate for system-wide accountability for WPS in the following key areas and advancing relevant recommendations made by the independent assessment in this regard.

Senior UN leadership must be held accountable for implementation of WPS. As underlined by the independent assessment, there are currently no repercussions for senior leadership who fail to fully implement their WPS obligations, consider WPS a priority concern, or who perform below a minimum standard on gender. It notes that “progress on the WPS agenda requires moving beyond relying on individual will, to proper system-wide institutionalization of accountability.” This applies to all senior leaders, including the heads of UN departments, offices, programs, funds; peacekeeping, political and peacebuilding missions; and special and personal envoys deployed in specific conflict situations. For example, Special Envoys should emphasize the importance of including women in delegations when they invite conflict parties to negotiations and also ensure they are updating the Security Council on progress in this respect. The heads of the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) and Department of Peace Operations (DPO) should prioritize the implementation of internal gender strategies, which mandate the mainstreaming of gender across the work of each office. Special Representatives and their teams are required to adhere to a range of operating procedures that require regular consultation with civil society organizations, including women’s rights and women-led organizations, in carrying out work across the entire mandate of a peace operation. The strength of these internal policies, however, is undermined by the lack of repercussions for senior leadership who uphold them. Finally, in relation to the public statements and priorities of the Secretary-General, it is also important to recognize that achieving parity within the UN system and in peacekeeping should be recognized as distinct priorities that are not the fulfillment of the full scope of WPS provisions and are not a substitute for integrating a gender perspective into the work of relevant UN entities.

UN leadership and entities must be held accountable for women’s direct participation in peace processes and the implementation of peace agreements. There is growing evidence that women’s participation in peace negotiations increases the durability of peace and that deals reached without their inclusion do not last. However, too often, ad hoc attempts to include women in symbolic, observer or advisory roles are held up as achievements rather than as stop-gap measures that have become necessary due to failure to directly include women in formal and structured ways from the beginning of a peace or political process. Advisory roles should be recognized as complementary, not as a substitute for direct participation, and should never be pursued as the primary engagement strategy by any UN entity. Special Envoys must be held accountable for failing to execute direct participation strategies and mediation support teams must include gender advisers as mandatory. Further, Special Envoys and their teams must take active steps to analyze barriers to women’s participation and identify entry points, and must be made to report on what specific measures were implemented to promote women’s participation. Failure to ensure accountability for taking concrete steps to facilitate women’s direct participation means that women’s participation will be demoted in favor of patriarchal philosophies of mediation that prioritize engagement with warring parties and cessation of conflict over inclusive peace processes.

Peace agreements must include robust, comprehensive gender provisions. As noted in the independent assessment, the majority of agreements do not include provisions on women, girls or gender, and in 2018, none of the UN-led “ceasefire or peace agreements included gender-related or women-specific provisions.” The assessment also noted that the quality of gender provisions in recent agreements is inconsistent. These alarming downward trends point to the need for dedicated attention to ensuring gender-inclusive processes and agreements, especially those led, co-led or otherwise supported by the UN.

Gender advisers and gender-sensitive conflict analysis must be prioritized and resourced. In 2018, 10 out of 15 peacekeeping missions had gender units, with only three senior gender advisers. Further, only eight of these units were reporting directly to the offices of the Heads of the Mission, as called for in the 2015 peacekeeping operations review. Gender advisers are critical to ensuring gender analysis is conducted, prioritized and funded, and that the UN system is therefore able to effectively respond to situations of conflict that are impacting the rights of women and girls. Our analysis reveals that having a mandate to address WPS correlates with the almost universal inclusion of some information on WPS in reporting. As a result, it is clear that there is an ongoing need for the Security Council to explicitly include provisions in future mandates that call for WPS to be mainstreamed, in addition to component-specific provisions on women’s meaningful participation and women’s and girls’ protection including in disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR), security sector reform (SSR), rule of law, and protection and monitoring of human rights. Despite emphasizing this point across all three peace and security reviews, the independent assessment reported “defunding and downgrading of gender adviser posts” within peacekeeping missions between 2016 and 2018, and that as of June 2019, only four of the 14 peacekeeping missions had senior gender adviser posts at the P5 level. Every peacekeeping mission must have senior gender advisers, who should be located in the offices of Special Representatives and Envoys. It is important to note that the responsibility for implementing WPS provisions in mandates does not lay solely with gender advisers, women’s protection advisers, gender focal points, or any other gender experts. The ultimate responsibility for the mainstreaming of WPS must lie with the mission leadership as prescribed by Resolution 2242 (2015).

Consultations with civil society by peace operations must be regular, mandatory and meaningful. Currently, consultations with women-led civil society by peace operations missions are neither “mandatory nor systematic, and there is no evidence of how it then informs further action.” Our analysis shows that missions with a mandate to engage with women’s groups and civil society organizations reported on such engagement more frequently and in more detail than those missions lacking a specific mandate for engagement.

WPS must be prioritized and resourced across the UN system. Another key deficit contributing to poor implementation of the WPS agenda by the UN system is the “degree to which gender and WPS is prioritized and resourced.” There is a need to double UN funds dedicated to gender equality more broadly and specifically to WPS. The UN target of 15% of funds to be earmarked for programs that further gender equality and women’s empowerment in peacebuilding contexts by 2020 should be a minimum first, and not a final, target. The funding provided under this target should be long-term, and the target should also be accompanied by indicators about the accessibility of funds to grassroots women’s organizations and the extent to which local women’s organizations have been included in priority and program design. Full implementation requires adequate, sustained and predictable resourcing of the WPS agenda, including funding to local civil society implementing the agenda.

Facts

How is senior UN leadership currently reporting on women’s meaningful participation?

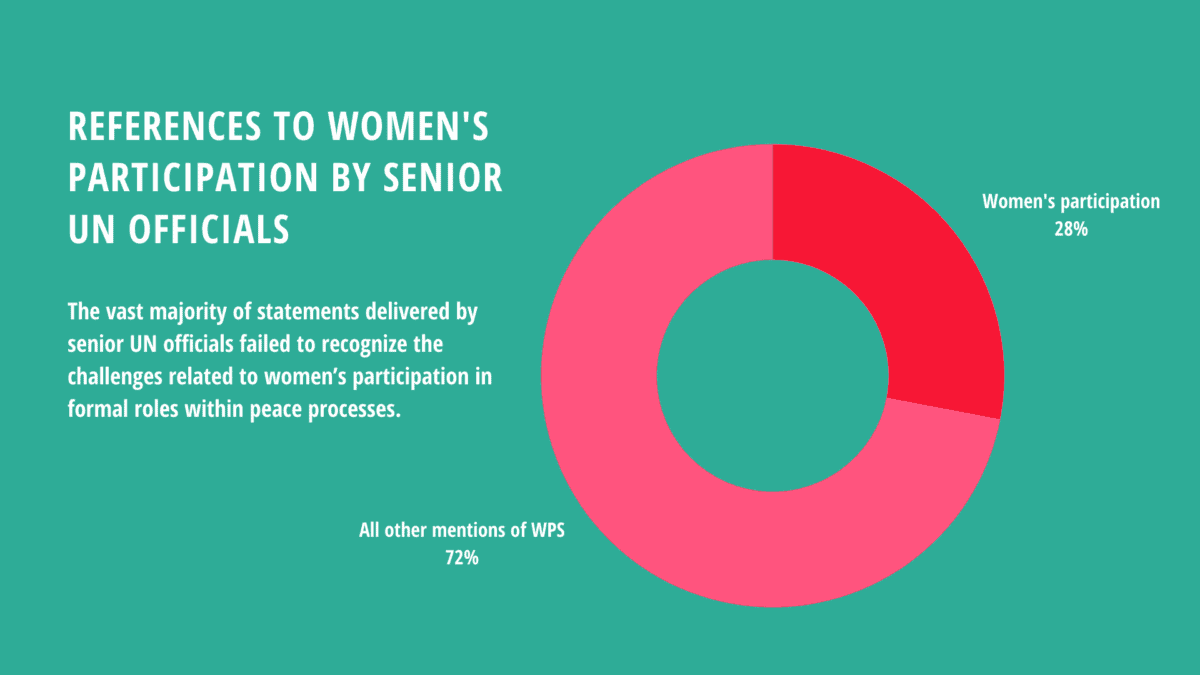

Our analysis of the statements delivered by senior UN officials — namely, Special Representatives and Special Envoys — during meetings on nine country-specific situations in 2019 revealed that while most statements referenced women in some way, only 28% of those references were to women’s participation.[2] In line with their obligations under Resolution 2122 (2013), senior UN officials speaking during meetings on Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen provided the most concrete examples of specific efforts undertaken to engage with women and women’s groups, or recognized the important work being done by women’s groups in conflict resolution and peace processes. Although these senior UN officials spoke of efforts to engage women in informal mechanisms parallel to peace processes, the vast majority of statements failed to recognize the challenges related to women’s participation in formal roles within peace processes. There was recognition that it was important for women to participate formally, but almost a universal failure to identify the barriers to this participation.

Notably, senior UN officials speaking during meetings on CAR, DRC, Libya, Mali and Sudan spoke the least about women, peace and security overall, and further largely overlooked issues related to women’s participation.

Importantly, the majority of more substantial references were delivered by senior UN officials who have been particularly engaged with civil society, including women’s groups.

Recommendations

- Hold UN senior leadership accountable for WPS implementation. As advised by the independent assessment, the Secretary-General should commit to updating and making publicly available the compacts for senior leadership — all Special Envoys, Special Representatives to the Secretary-General, Resident Coordinators, Humanitarian Coordinators, Senior Advisers and other senior managers throughout the UN system — to reflect WPS as a key priority. Special Envoys should be requested to regularly report on their efforts to explore all available avenues to support the direct participation of diverse women in peace processes. In addition, Special Envoys should also publicly report on the gender composition of all negotiating parties.

- Prioritize, resource and politically support recruitment of gender advisers.[3] Prioritize and fund systematic recruitment and appointment of senior women’s protection advisers and gender advisers, and ensure they are located in the offices of all Special Representatives, Special Envoys and strategic assessment or review teams. Publicly report on deployment in order to ensure greater transparency on which posts are filled and which remain vacant.

- Fund gender equality and the WPS agenda. Meet the target of 15% of funds being earmarked for programs that further gender equality and women’s empowerment in peacebuilding contexts by 2020, and increase the target to 30% after 2020 with a view to further increasing it in the future.

- Ensure all peace operations have robust, holistic and comprehensive mandates to address WPS. Include provisions in all peace operations mission mandates that call for gender to be a cross-cutting issue, in addition to specific language with regard to the need for effective protection and full, equal and meaningful participation of women and girls within each mandate component. Additionally, the Security Council should explicitly require the integration of WPS as a cross-cutting issue in all reports of the Secretary-General on country-specific and regional situations, as well as thematic issues; this analysis should be accompanied by sex-, disability- and age-disaggregated data. Further, all peace operations must be mandated to consult regularly with diverse women’s groups as part of implementing their WPS mandate.

[1]UN Security Council, Women and peace and security: Report of the Secretary-General (S/2019/800), 2019.

[2]The nine country situations which were the subject of our analysis were: the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Libya, Mali, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

[3]See independent assessment.