Human rights defenders, peacebuilders and civil society space

“The threat of reprisals and retaliation for participating in politics or carrying out human rights work, combined with a lack of accountability for such acts…has effectively forced women out of public life.”

Marwa Mohamed, UN Security Council Briefing on Libya, September 2019

Key Messages

Women human rights defenders (WHRDs) refer to all women — including Indigenous defenders, defenders from cultural, ethnic and religious minorities, those with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, gender expression and sex characteristics (SOGIESC) — who defend any human rights, as well as people of all genders who defend gender equality and women’s rights.[1] The work of WHRDs and peacebuilders is integral to the promotion of human rights, prevention of conflict and ensuring sustainable and inclusive peace.

WHRDs and peacebuilders face threats and attacks due to their real or perceived identities and the issues they advocate for, particularly when they are perceived as challenging patriarchal norms or existing structures of power. In 2019, 40 WHRDs were killed for advocating for the protection and promotion of human rights.[2] WHRDs and peacebuilders today work in environments that are hostile to many of the issues they work on — including gender equality, sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and the rights of people with diverse SOGIESC, which compounds the effects of already closing space for civil society. Threats and attacks on HRDs in Colombia disproportionately impact Afro-descendant and Indigenous leaders, women leaders, and leaders promoting the Peace Accord.[3] Since 2016, approximately 23% and 9% of assassinated HRDs and social leaders, respectively, were Indigenous and Afro-Colombian, while 13.96% of total victims identified as women.[4] WHRDs have, therefore, increasingly become targets of violence and threats, including gender-based violence (GBV), in retaliation for their work.

Moreover, threats and attacks on WHRDs and peacebuilders serve as a deterrent to their participation and leadership, especially in contexts where women must already overcome cultural, political, economic or other barriers to entering public life.

There is also a clear trend of states using counter-terrorism or national security as a rationale to curtail anything that is perceived as dissent or criticism of governments, often presenting WHRDs as security threats. Increasingly, some states are trying to use the UN counter-terrorism architecture and the growing body of Security Council resolutions focused on counter-terrorism, as a basis for restrictions on civil society and crackdowns on HRDs, which can have far-reaching consequences as they place binding obligations on all countries.

Threats to HRDs and peacebuilders undermine global efforts to prevent conflict and sustain peace. The lack of recognition for the legitimate work of HRDs creates a context that enables all kinds of attacks to take place. Member States must, therefore, not only ensure protection from reprisals, including for cooperating with UN bodies, but when required, speak out publicly against such attacks to send an unequivocal message that they will not be tolerated. It is vital that the Security Council and Member States publicly recognize and promote the legitimacy of the work of all HRDs and peacebuilders and the role they play in defending human rights and promoting peace and security.

Facts

How has the Security Council addressed civil society?

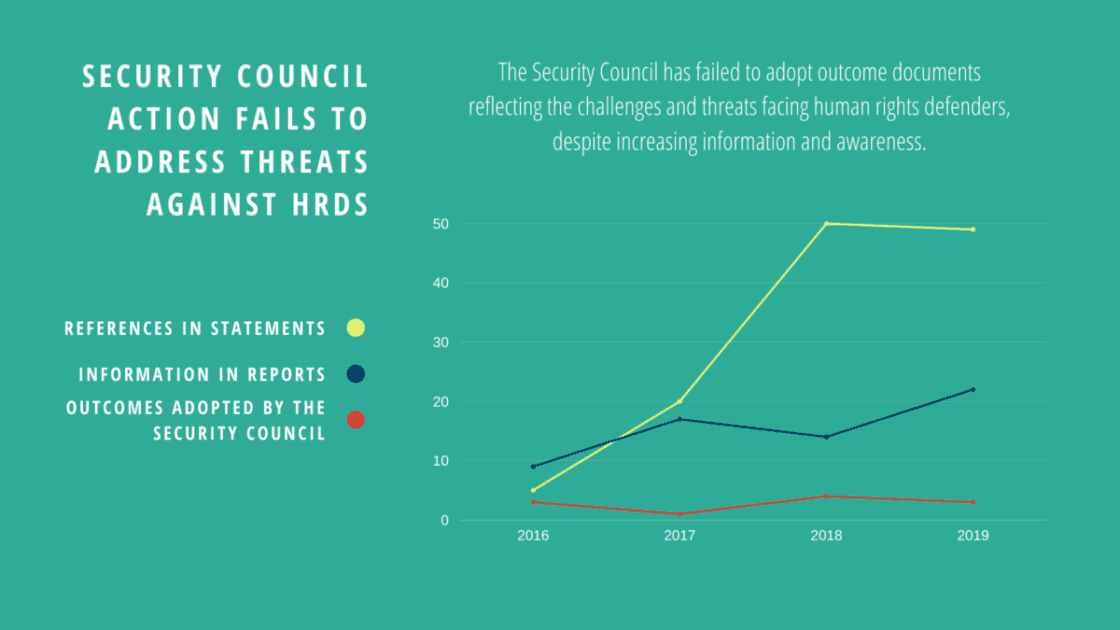

Over the last 20 years, the Security Council has reinforced, acknowledged and highlighted the role of civil society more than 500 times in adopted resolutions and presidential statements, calling for Member States and the UN to work with civil society in conflict prevention efforts, peacebuilding, provision of humanitarian assistance and peace processes.

Yet, despite this broad acknowledgement, the Security Council has failed to adequately address the threats to civil society, including women’s groups, or human rights defenders (HRDs), who are often targeted directly for violence or harassment, including through the use of security or counter-terrorism legislation. This mismatch between stated ideals and action is one of the clearest gaps in the Security Council’s implementation of the WPS agenda. There were no references to women human rights defenders (WHRDs) in any outcome documents adopted by the Security Council in 2018 or 2019; further, references to HRDs decreased in outcome documents in 2019.[5]

Impact of counter-terrorism and security legislation on civil society

- More than 140 countries around the world, the majority of the world’s population, have counter-terrorism or security legislation that can be utilized to target civil society and HRDs.[6]

- Between 2005 and 2019, 66% of all communications to the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism were on the use of counter-terrorism laws and policies to restrict civil society space, indicating an intentional targeting of civil society by governments around the world.[7]

- According to Front Line Defenders, 58% of the cases in which they provided direct support to HRDs in 2019 included charges under security or counter-terrorism legislation.[8]

Recommendations

- All relevant UN entities and experts, including senior officials, such as Special Representatives of the Secretary-General, Humanitarian Coordinators and Resident Coordinators, should issue statements of condemnation in response to violent rhetoric and crackdowns on civil society, including on WHRDs and peacebuilders.

- The UN must, in the context of its conflict prevention and early warning efforts, and its human rights monitoring and reporting, monitor all attacks and threats of violence targeting WHRDs and peacebuilders. This should occur across the UN system, including by peace operations. Attacks and violence should be taken as a sign of escalating instability or potential conflict. Monitoring efforts should include robust data collection that is intersectional, disaggregated and considers the identity of the HRD, as well as the issues and populations they work with. Information and analysis must be included in reports of the Secretary-General on country- and region-specific situations, and provide analysis of any attempts to restrict the activities of women civil society leaders and HRDs. As part of efforts to monitor these threats, UN system entities at the local level must consult with diverse women’s civil society organizations and HRDs. In contexts where legal recognition and registration of organizations working on these issues is impossible, adopt alternative measures to ensure diverse inclusion including, but not limited to, consulting with organizations inside and outside of the country that have partnerships with organizations and individuals working in these areas.

- Support the participation of civil society briefers, including peacebuilders and HRDs, at the Security Council. Actively invite and support diverse women civil society briefers on all country situations, prioritizing invitations to briefers who have been independently selected by civil society organizations, networks and coalitions. Council members should provide political and financial support as required, including any assistance or diplomatic support to obtain visas in order to brief UN bodies such as the Security Council. With a view to coherence and inclusivity, consider more diverse and independent sources of information from women-led and women’s rights groups, as part of their deliberative process, including civil society alternative reports submitted to other UN bodies, such as the Committee on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the Universal Periodic Review, as well as formal and informal civil society briefings.

- Include provisions in the mandate of peace operations requiring the monitoring and reporting of attacks, threats and killings of HRDs, including WHRDs, and further require all peace operations to meaningfully consult with diverse women’s civil society organizations in all aspects of mandate implementation, including conflict prevention, protection of civilians, peacebuilding, and electoral support, as called for in Resolution 2122 (2013) and outlined in the Department of Peace Operations’ Gender Responsive United Nations Peacekeeping Operations Policy and the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs’ Women, Peace and Security Policy.

- Prevent reprisals against civil society representatives, including peacebuilders and HRDs, for cooperating with UN bodies. Recognition of the legitimacy and value of HRDs in promoting peace and security can be an important deterrent against attacks or reprisals against them, and can contribute to an enabling environment for them to continue to carry out their work safely in the long-term. For this reason, public recognition of the legitimate role of HRDs, including women’s civil society, and condemnation of all attacks against them, including in the context of counter-terrorism efforts or for cooperating with UN bodies such as the Security Council, can be expressed in outcome documents and public statements. When reprisals occur for engaging with UN bodies, the agency, concerns and safety of the HRD, and the context in which they work, must be at the center of any response, which should be gender-sensitive and crafted in consultation with the defender at risk. Finally, it is critical that any avenues for civil society participation or contributions to the work of UN bodies remain dedicated and independent spaces for women civil society, and any efforts to mitigate or respond to reprisals must never compromise their participation. Any response by the Security Council or other UN bodies must comply with international standards, principles and recommendations made by relevant UN experts such as the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders.

- Reinforce and support the recommendations of experts, such as the Special Rapporteur on Counter-terrorism and the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders, in relevant discussions and outcomes on country- and region-specific situations, including by calling for governments to refrain from using counter-terrorism and national security policies to target and restrict HRDs, including WHRDs.

- Ensure a safe and enabling environment for civil society in which WHRDs are protected, supported and their legitimacy is recognized. Adopt and implement legislation that recognizes and protects the rights of WHRDs, peace activists and humanitarian personnel, such as freedom of expression, association, assembly and other civil liberties in law and practice. Eliminate all laws that restrict and criminalize the work that HRDs do, as well as the issues and populations with which they engage, including counter-terrorism and national security legislation, which is often used to unduly attack, restrict and otherwise criminalize the work of HRDs. Adopt and implement gender-sensitive protection measures to enable both the participation and safety of WHRDs.

- Defend civil society space: Call on all Member States to uphold international human rights and humanitarian law and refrain from enacting indefinite or disproportionate emergency measures that limit or entirely curtail the right to movement, assembly and information, or impose undue restrictions on civic space or the work of civil society and HRDs, including women’s rights organizations, as part of pandemic response.

[1] ISHR, Reprisals and the Security Council, 2019. https://www.ishr.ch/news/reprisals-new-ishr-policy-brief-reprisals-and-security-council

UNGA, Situation of women human rights defenders: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders (A/HRC/40/60), 2019.

UNGA, The Declaration on human rights defenders (A/RES/53/144), 1998.

[2] Front Line Defenders, Front Line Defenders Global Analysis 2018, 2019. https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/sites/default/files/global_analysis_2018.pdf

[3]Instituto Kroc de Estudios Internacionales de Paz, Tercer Informe sobre el Estado de Implementación del Acuerdo de Paz de Colombia, 2019, p.103. https://kroc.nd.edu/assets/321729/190523_informe_3_final_final.pdf

[4] Indepaz, Separata de actualización, Todos los nombres, Todos los rostros, 2019, pp. 25, 28. http://www.indepaz.org.co/wpcontent/uploads/2019/05/SEPARATA-DE-ACTUALIZACIO%CC%81Nmayo-Informe-Todas-las-voces-todos-los-rostros.-23-mayo-de-2019- ok.pdf

[5]NGOWG Policy Brief 2018

[6]CSIS, Counterterrorism Measures and Civil Society: Changing the Will, Finding the Way, 2018. https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/180322_CounterterrorismMeasures.pdf?EeEWbuPwsYh1iE7HpnS2nPyMhev21qpw

[7]Ní Aoláin, Impact of measures to address terrorism and violent extremism on civic space and the rights of civil society actors and human rights defenders: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism (A/HRC/40/52), 2019. https://undocs.org/A/HRC/40/52

[8]Front Line Defenders, Front Line Defenders Global Analysis 2018, 2019. https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/sites/default/files/global_analysis_2018.pdf