By Kaavya Asoka

Six months into 2020, during what should be a celebratory year for women’s civil society marking the 20th anniversary of Resolution 1325 (2000), their voices are barely heard at the UN Security Council. Why?

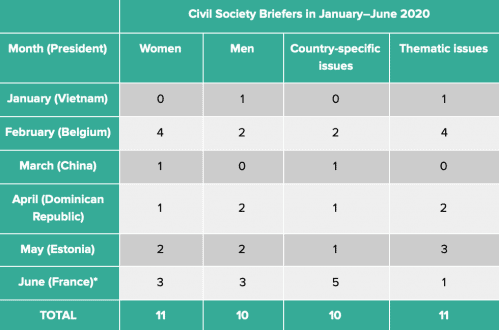

Since 1 January 2020, the Council has held 53 formal meetings and 64 open VTCs during which 21 civil society briefers have delivered statements, 11 of whom were women. This represents a 38.9% decrease compared to 2019.

The current limitations facing the Security Council as it conducts its work virtually undoubtedly pose challenges to civil society participation. However, in the more than three months since the Council began working remotely, it has become clear that these are not merely technical challenges but a lack of political will — a deprioritization of the voices of independent civil society despite Council member’s claims of women’s critical role in ensuring peace and security.

The NGOWG has nominated 18 civil society representatives under all six presidencies to brief the Council on 12 different agenda items, pursuant to the Security Council’s commitment to invite women civil society representatives to brief during country-specific meetings under Resolution 2242 (2015).

Warnings from civil society about exclusion

On April 18, along with 30 other human rights, humanitarian, development and women’s rights organizations, we wrote to the President of the Security Council to raise concerns around the transparency of the work of the Security Council and obstacles to the effective participation of civil society due to changes to its working methods under the COVID-19 pandemic. On May 11, we followed up with supportive Council members to continue to raise the alarm regarding what we saw as a continuing pattern of exclusion. In parallel, other civil society organizations have raised similar concerns around barriers to inclusive and meaningful engagement of civil society as well as risks of intimidation and reprisals in the context of other virtual UN meetings, including the High-Level Political Forum and the Human Rights Council.

However, despite the repeated warnings issued by dozens of organizations from around the world, the pattern of exclusion continues. This trend must be urgently reversed, lest we lose the gains made over the last four years.

In response to this downward trend, since early April, we have continued to facilitate informal briefings between women’s civil society representatives and Security Council members on Colombia, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Yemen, Mali, the Central African Republic and South Sudan. With our support, Council members have heard from 14 women with expertise on nine different countries over the course of the last two months.

However, we are concerned that these informal channels will become a replacement for civil society participation in the formal work of the Security Council. As we have repeatedly raised with Council members: women civil society representatives must not be relegated to only informal spaces, where they will not be able to share their perspectives with the full Council membership. This is counter to the Council’s own commitments as laid out in Resolution 2242 (2015).

The Security Council must live up to its own promises

Over the last 19 years, the Security Council has reinforced, acknowledged and highlighted the role of civil society over 500 times, calling for Member States and the UN to work with civil society in conflict prevention efforts, peacebuilding, provision of humanitarian assistance and peace processes[1] and has, on multiple occasions, recognized the role of civil society, particularly women’s groups, as crucial interlocutors in conflict situations.

Since the adoption of Resolution 2242 (2015), the number and diversity of women civil society briefers at the UN Security Council has increased; from nine women in 2016 to 40 in 2019. These briefers bring a wealth of expertise and experience to the Security Council, enriching its discussions by highlighting marginalized perspectives and raising issues that would otherwise be overlooked in favor of political considerations. The importance of these briefings, however, goes far beyond numbers.

Issues related to women, peace and security are less likely to be raised if they aren’t raised first by a civil society briefer.[2] Briefings by civil society leaders expand the understanding of policymakers related to the role of women’s organizations in mediating and negotiating local disputes or advocating on behalf of their communities in parallel to formal peace processes. The tendency of the international community to focus largely on high-level, formal processes is detrimental to a deeper understanding of the complexity of crisis situations and, importantly, the central role of women peacebuilders, human rights defenders and women’s civil society organizations on the frontlines providing essential services and resolving conflicts. This means that without these briefings, the critical perspectives of individuals and communities who are directly affected by the Council’s decision-making are not being heard, nor are Council members making these decisions with a full picture of the situation on the ground.

Civil society can often be more effective than international actors in settling local disputes or providing services such as humanitarian and development assistance — these are, after all, their own communities, and they have valuable insight into what drives local conflicts as well as the best solutions. Yemeni activists, for example, have recently highlighted that the Mothers of Abductees Association, who were excluded from the Stockholm peace talks, have negotiated the release of more than 940 arbitrarily detained persons — meanwhile, there has been no progress through the UN-led process to date. The Security Council only stands to benefit from hearing these perspectives — and learning from and supporting such strategies — when civil society contributes to its discussions. This is also why we have strongly advocated for women-led society to be actively consulted and included in shaping responses to COVID-19 and emphasized the importance of women’s leadership in designing and implementing pandemic responses.

Civil society briefers take risks to share their perspectives in public fora — it is therefore essential that they are heard at the highest levels, and that their recommendations are acted upon. As an organization that has supported 47 briefers in Security Council meetings and open debates since 2009, we are acutely aware of the risks that civil society take when they criticize their governments or parties to conflict and challenge social and gender norms. They work in dangerous contexts, relentlessly undertaking courageous work to serve their communities — defending human rights, delivering life-saving services to survivors of gender-based violence, advocating for the protection of women’s rights in law and practice, and undertaking direct negotiations with armed actors on the local level, to name but a few. In 2019 alone, at least three civil society briefers experienced a backlash following their briefings to the Security Council as a direct result of raising issues related to attacks on civil society, enforced disappearances, gender-based violence and systematic exclusion of women from public and political processes. Each briefer was harassed via social media, and one briefer was the subject of a formal letter of complaint by their government to the President of the Security Council. There are, of course, many others.

Civil society representatives brief the UN Security Council in the hope that the Council will not simply listen to them but hear what they have to say. But if their recommendations are not acted upon, the risks they face are all for nothing.

Concerns are now deepening among civil society that the current deprioritization of civil society access and participation will be exploited by Security Council members that have historically been hostile to their participation in the first place upon returning to formal, in-person meetings. Supportive Council members must act now to ensure that civil society is heard and that their concerns are reflected in Council discussions. Security Council members must elevate their voices, their work and their legitimacy, and lay the important groundwork for civil society, human rights defenders and peacebuilders to be recognized and valued, to protect civic space, and to prevent attacks and reprisals rather than responding to them after they have taken place.

We therefore urge the Security Council to prioritize the following:

- In line with Resolution 2242 (2015), ensure women civil society briefers are invited to brief the Security Council during country-specific meetings, including during open VTCs, and not limited to briefing only during thematic open debates, informal briefings or side events.

- Maintain the foundational principle of independence by ensuring that civil society briefers are selected and supported by civil society organizations, and not only hand-picked by Security Council members.

- Ensure that the recommendations put forth by civil society briefers are acted upon in all outcome documents and statements delivered by Security Council members, and track and follow implementation of these recommendations as called for by the UN Secretary-General in 2019 as one of six immediate actions to be taken by Security Council members.

As a coalition dedicated to gender equality and women’s human rights, the voices of grassroots women’s civil society are at the heart of the NGOWG’s work; they should be at the center of the Security Council’s work as well. In a year that was meant to resonate with the voices of women — 40 years since the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), 25 years since the adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, and 20 years since the adoption of Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) — the Security Council can and should do better. If not now, when?

Kaavya Asoka is the Executive Director of the NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security.

[1] Women, peace and security (S/RES/1325 (2000), OP 15; S/RES/1820 (2008), OPs 11, 13; S/RES/1888 (2009), PP, OP 4, 9, 26; S/RES/1889 (2009), OPs 6, 9-11, 18; S/RES/1960 (2010), OP 8; S/RES/2106 (2013), OPs 11-12, 19, 21; S/RES/2122 (2013), OPs 6, 7(b), 11; S/RES/2242 (2015), OPs 1-3, 5(b)-(c), 16); S/PRST/2010/22; S/PRST/2012/23; S/PRST/2011/20; S/PRST/2007/40).

[2] NGOWG on WPS, Mapping Women, Peace and Security in the UN Security Council: 2018, 2019. https://www.womenpeacesecurity.org/files/NGOWG-Mapping-WPS-in-UNSC-2018.pdf